Who’s Who

The following is a list of people mentioned on this site. Click on any name below to jump to a brief biography:

- John Abt

- Dean Acheson

- Bert Andrews

- Max Bedacht

- Elizabeth Bentley

- Adolf A. Berle, Jr.

- Dr. Carl Binger

- Joseph Boucot

- Louis Budenz

- William C. Bullitt

- William M. Bullitt

- Col. Boris Bykov

- James F. Byrnes

- David Carpenter

- Claudie Catlett

- Perry Catlett

- Raymond Catlett

- Esther Chambers

- Whittaker Chambers

- Henry Collins

- Malcolm Cowley

- Rev. John F. Cronin

- “George Crosley”

- Claude Cross

- Charles F. Darlington

- John F. Davis

- John W. Davis

- Lucy Elliott Davis

- Donald Doud

- Laurence Duggan

- John Foster Dulles

- Evelyn Ehrlich

- Thomas Fansler

- Edwin H. Fearon

- Ramos C. Feehan

- Noel Field

- Plum Fountain

- William Reed Fowler

- Felix Frankfurter

- Henry W. Goddard

- Donald Hiss

- Priscilla Hiss

- Thayer Hobson

- Timothy Hobson

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

- J. Edgar Hoover

- Stanley K. Hornbeck

- Felix Inslerman

- Matthew Josephson

- Samuel H. Kaufman

- J. Kellogg-Smith

- Alfred Kohlberg

- Chester Lane

- Myles J. Lane

- Louis Leisman

- Isaac Don Levine

- Nathan I. Levine

- Ira Lockey

- Benjamin Mandel

- William Marbury

- Hede Massing

- Elizabeth McCarthy

- John McDowell

- Edward C. McLean

- Karl E. Mundt

- Thomas F. Murphy

- Edith Murray

- Dr. Henry A. Murray

- Richard M. Nixon

- Daniel Norman

- Gerald Nye

- Samuel J. Pelovitz

- Jozsef Peter

- William Ward Pigman

- Lee Pressman

- John Rankin

- William Remington

- Franklin Victor Reno

- William Rosen

- Samuel Roth

- George Norman Roulhac

- Francis B. Sayre

- Meyer Schapiro

- Horace W. Schmahl

- Harold Shapero

- George Silverman

- Nathan Gregory Silvermaster

- Herbert Solow

- William Spiegel

- Edward Stettinius, Jr.

- Robert E. Stripling

- Lloyd Paul Stryker

- J. Parnell Thomas

- Martin Tytell

- Robert von Mehren

- Henry Julian Wadleigh

- Harold Ware

- Nathaniel Weyl

- Raymond Whearty

- Harry Dexter White

- Nathan Witt

- David Zablodowsky

- Dr. Meyer A. Zeligs

BIOGRAPHIES

John Abt

John Abt

Abt was alleged by Whittaker Chambers to have been a member of the so-called “Ware Group,” an “underground cell” of Washington-area communists that Chambers at first claimed had not been involved in espionage.

Abt was a lawyer who, like Alger Hiss, worked at the Agricultural Adjustment Administration. When subpoenaed by HUAC, he refused to answer questions, but years later discussed Chambers’ charges in his autobiography, Advocate and Activist. In the book he says he knew Chambers (who for some reason spoke with a German accent) only casually, but discusses the “Ware Group” at some length: He acknowledges that its members were communists, but says it met only to discuss policy and theory and was not an “underground” organization. Moreover, it was never known as the “Ware Group.” Abt, however, does not discuss whether Hiss was associated with the group.

According to the Vassiliev Notebooks, a 1944 GRU memo stated that the “Ware Group”’s principal members “had never been GRU agents.”

Dean Acheson

Dean Acheson

Acheson served as Secretary of State in the Truman administration. His statement that he wouldn’t “turn his back” on his colleague and friend Alger Hiss hurt him politically.

In January 1949, on the day of his confirmation as Secretary of State, Acheson read a prepared statement to the Senate, containing “an assertion of personal friendship for the Hiss brothers, a staunch defense of Donald Hiss and a purpose to leave Alger Hiss to the courts.” Alger Hiss was then preparing for his first perjury trial. Donald Hiss had worked directly for Acheson during the war, at one point as his Executive Secretary, and had become his partner in the Washington law firm later known as Covington & Burling. “He served me and he served the country with complete fidelity and loyalty,” Acheson said. “He and I became, and we remain, close and intimate friends. He is now my partner, with everything that that relationship implies.”

Bert Andrews

A Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, Andrews became a behind-the-scenes adviser to Richard Nixon (and a main conduit for his leaks) when the Hiss Case broke before HUAC. He later told his own story, co-authored with Peter Andrews, in A Tragedy of History: A Journalist’s Confidential Role in The Hiss-Chambers Case: Robert B. Luce, Washington D.C., 1962.

Max Bedacht

Bedacht was an active member of the Communist Party. Whittaker Chambers claimed Bedacht recruited him into the underground. Bedacht admitted to Party membership but in 1948 denied Chambers’ charge before the the New York grand jury investigating espionage, saying he had nothing to do with underground activities.

Bedacht also said he had had little to do with Chambers when he met him years before in the office of the communist-leaning magazine New Masses. He was not indicted for perjury. An excerpt from Bedacht’s memoirs tells more.

Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Bentley

The so-called “Red Spy Queen,” Bentley (1908-1963), a Vassar graduate, was a self-confessed former courier for Russian agents who in the late 1940s became, along with Whittaker Chambers, one of the era’s two most celebrated anti-communist witnesses. Bentley appeared in World War II Venona cables as “Umnitsa” (“Clever Girl”) and as “Mirna,” and was awarded the USSR’s Order of the Red Star in 1944, but began cooperating with the FBI in 1945. She testified before HUAC on July 31, 1948 that former Assistant Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White and 31 other government employees were spies. Bentley told the FBI that she had heard through a secondhand source that there was a spy in the State Department, but did not name Alger Hiss, and did not testify at his trials. She was not “always scrupulous with the truth,” a biographer has noted, and none of the 32 people she denounced before HUAC was convicted of espionage.

Bentley died of acute alcoholism in 1963. See the entry on William Remington for more on the impact of her testimony.

Adolf A. Berle, Jr.

Adolph A. Berle Jr.

In 1939 Berle, then an Assistant Secretary of State and the department’s chief security officer, met with Whittaker Chambers at the request of Isaac Don Levine, an anti-communist magazine editor. Chambers’ conversation with Berle was the first time he made any charges about communist activities to government officials. Berle’s notes on the meeting, in which Alger and Donald Hiss were mentioned, were introduced at the Hiss trials.

After the trials, Berle told Hiss’s attorney, Chester Lane, that Chambers was not convincing or clear about Hiss’s communist connections. Berle said Chambers had told him only that the Hiss brothers were targeted for recruitment by Party members for a study group in Washington. Lane’s memorandum of the conversation explains.

Berle’s notes also indicated that Chambers told him he left the Party in 1937. The government documents introduced into evidence – documents that Chambers said he got from Hiss – were dated 1938. For more on this discrepancy, read about Chambers’ break with the Communist Party.

Dr. Carl Binger

At the time of the Hiss trials, Binger was a practicing psychiatrist and an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at the Cornell University Medical School. After observing and analyzing Whittaker Chambers’ activities and writings, he testified for the defense that Chambers was a psychopathic personality. His theories were dismissed by Prosecutor Thomas Murphy on cross examination.

Joseph Boucot

Under questioning in pre-trial depositions for Hiss’s libel suit against him, Whittaker Chambers cited a long visit that he said Priscilla Hiss had paid to Chambers’ cottage in Smithton, New Jersey, to support his claim that a close relationship existed between the two families. Chambers said their landlord, Joseph Boucot, would back up his story, because he had been introduced to Mrs. Hiss.

The defense found Boucot, who lived only 100 feet from Chambers’ summer cottage, and questioned him. Boucot said he never met Mrs. Hiss. Chambers then said he was no longer so sure that Mrs. Hiss had met Boucot, but Esther Chambers still testified that Priscilla Hiss did visit. Boucot and his sister both testified that this was untrue.

Louis Budenz

Louis Budenz

Budenz, a former editor of the Daily Worker who later became an influential anti-communist, testified before HUAC in 1948 that he had heard Hiss’s name mentioned in communist circles around 1940. He did not testify at either of Hiss’s perjury trials. He did appear as a witness in 60 investigations into possible subversion, but gained a reputation for what one commentator has called “frequent exaggerations and falsifications.” He does not appear in the Venona cables, but the Vassiliev Notebooks indicate he may have been part of a 1930s Soviet foreign intelligence group aimed at Trotskyites.

William C. Bullitt

Bullitt served as the first US ambassador to the Soviet Union and later was ambassador to France. In 1952, he said he had heard in 1939 that the Hiss brothers were Soviet agents. The source of that information, according to Isaac Don Levine, was Whittaker Chambers; Levine said he had briefed Bullitt on Chambers’ 1939 conversation with Adolf A. Berle.

William M. Bullitt

Bullitt (a relative of William C. Bullitt) was a former Solicitor General and a trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. During the first Hiss trial, he wrote and distributed to the press a pamphlet attacking the veracity of Hiss’s testimony.

Col. Boris Bykov

Bykov was allegedly Chambers’ boss in the communist underground, succeeding J. Peters. Chambers said Bykov instructed him to begin collecting documents to be passed on to the Soviet Union.

Chambers’ accounts of his relationship with Bykov were amplified over years of retelling. Bykov was not mentioned by Chambers in his 1939 interview with Adolf Berle, according to Berle’s notes from the session. In his interview with the FBI in 1942, Chambers said he had met Bykov but only in passing. He told a similar story to the FBI in a 1945 interview.

Boris Yakelovich Bukov, as Bykov was in fact known, spent two decades in Russian military intelligence (1920-1941), and in 1935 was given a rank equivalent to Colonel. He was a rezident in the U.S. from mid-1935 to the end of 1938. Only Chambers’ accusations link him to Bukov, but it is known that the GRU considered Bukov’s U.S. work “extremely fruitful.”

James F. Byrnes

Byrnes became Secretary of State under Truman, succeeding Edward Stettinius. In 1945 Roosevelt invited Byrnes, at that time still a senator from South Carolina, to be part of the Yalta delegation (of which Hiss was also a member), in an effort to include a conservative viewpoint. Byrnes later publicly opposed some of the Yalta agreements.

In 1946, Byrnes advised Hiss to talk to the FBI about rumors that he was a secret communist. Hiss subsequently was interviewed by the FBI.

David Carpenter

Carpenter was one of the people alleged by Whittaker Chambers to have photographed documents for transmission to Russia. Julian Wadleigh said he would hand State Department documents directly to Carpenter, who would photograph and return them. Carpenter refused to answer questions before the grand jury.

Claudie Catlett

Catlett, whose nickname was Cleide, was one of the Hisses’ former maids. She testified at both trials, recalling among other things that a man named “Crosby” (supporting Alger Hiss’s contention that Whittaker Chambers used the pseudonym “George Crosley”) visited the family when they lived on P Street. She also said he visited the house when the Hisses were not home and that, much later on, Chambers and the FBI visited her to solicit information about the Hisses’ household. She testified about receiving an old typewriter from the Hisses. Before the trials, she was interviewed several times by FBI agents and became confused about the date that the Hisses gave her the typewriter. For more on this important issue, click here.

Perry Catlett

Claudie Catlett’s older son (sometimes called “Pat”) testified for the defense regarding the typewriter, saying at first that it was given to his family when the Hisses had moved from P Street (which means it would have been out of the Hisses’ house when the State Department documents were allegedly typed). On cross examination, his testimony was vague about the exact date. All three Catletts were interviewed by the FBI several times, and their testimony became confused as to when they had received the Woodstock.

Raymond Catlett

Claudie Catlett’s younger son was, according to trial observers, a “truculent” defense witness on cross examination, as he grew frustrated with repeated questioning on the typewriter issue. In the end, the Catletts’ confused testimony did little to help Hiss. Raymond, also known as “Mike,” was instrumental in helping the defense locate the Woodstock typewriter that it then placed in evidence, under the assumption that it had been the typewriter owned by the Hisses and later given to the Catletts.

Esther Chambers

The wife of Whittaker Chambers and a onetime devout “revolutionist,” Esther Chambers testified at both trials in full support of her husband. When asked by the prosecutor if her husband had said they were moving to Ypsilanti and her name was to be Hogan, she replied, “We would go to Ypsilanti and our name would be Hogan.”

Some of her testimony was contradictory, and at times she had difficulty remembering important dates, including the date of her husband’s departure from the Communist Party.

At the first trial, she was unable to recall her own wedding date, but remembered some 20 or so occasions when she said she got together with Priscilla Hiss. At the second trial, her recollections about the Hisses’ apartment were repeatedly found to be inaccurate.

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers

Hiss’s sole accuser, an accomplished writer, editor, and translator, was born Jay Vivian Chambers in Philadelphia in 1901.

By his own account, Chambers had a difficult childhood. His father, an illustrator, abandoned the family when Chambers was a boy. Chambers’ brother committed suicide at the age of 23. Chambers said he himself had attempted suicide several times during the course of his life.

During the Hiss trials, the defense demonstrated that Chambers had repeatedly embellished details and invented incidents in his life. His first biographer, Dr. Meyer A. Zeligs, a psychiatrist, years later pointed to a recurring pattern in Chambers’ life of befriending and then betraying people he felt drawn to.

In 1925, Chambers joined the Communist Party; he later said that he had served in the “underground” in the 1930s. The date of his departure remains a subject of dispute. Journalists such as William A. Reuben have delved into Chambers’ life and questioned the whole basis of his story that he committed espionage for the Soviet Union. Chambers, who in the 1930s translated a number of German books, including Bambi, was hired by Time magazine in 1939. He was a Senior Editor at Time when he publicly testified against Alger Hiss in 1948. Chambers’ autobiography, Witness, was a best seller in the 1950s. He died in 1961.

Chambers posthumously received the Medal of Freedom from President Ronald Reagan, under whose administration Chambers’ farm in Westminster, Maryland – the site of the pumpkin patch where Chambers dramatically hid the “Pumpkin Papers” in 1948 – became a National Historic Landmark.

For more on Chambers’ charges against Hiss, click here.

Henry Collins

Collins was a childhood friend of Alger Hiss’s who was also accused by Whittaker Chambers of participating in underground activities. Chambers said Collins was introduced to Col. Boris Bykov, his boss in the underground. Collins testified before the grand jury investigating espionage, denying Chambers’ charges.

Chambers testified before HUAC on August 3, 1948 that he collected Communist Party dues from Collins but would later contradict that testimony. Chambers’ August 7th testimony repeats his allegations about Collins.

Collins’ name turns up at one point in the Vassiliev Notebooks, but any possible involvement on his part with Soviet intelligence remains unclear.

Malcolm Cowley

A noted literary critic and historian, Cowley was drawn into the Hiss case because, in 1940, Whittaker Chambers had contacted him about reviewing books for Time magazine. Cowley recorded their conversation in his diary, noting among other things that Chambers had said that Francis B. Sayre, Alger Hiss’s boss in the State Department and Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law, was connected to the communist underground.

Cowley also noted the horrible condition of Chambers’ teeth (Hiss would be ridiculed for making similar comments eight years later) and that Chambers told him he had left the Communist Party in 1937. (Click here to read more about the controversy surrounding the date.)

Chambers, who had in his possession State Department documents which had been in Sayre’s office, would later say those papers came from Hiss, Sayre’s assistant. In subsequent statements, Chambers did not link Sayre to the underground.

Cowley testified for the defense at both trials and later said his testimony for the defense had significantly damaged his career. He later discussed his conversation with Chambers in a film by John Lowenthal. Listen to an audio clip of the conversation in our audio archive, or watch the full film.

Rev. John F. Cronin

An influential, politically conservative Catholic priest, Father Cronin prepared reports on American communists for the Catholic Church and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. In his reports, he named Alger Hiss as a Party member while in the Agricultural Adjustment Administration. Cronin’s source for this information was Whittaker Chambers. One of Cronin’s reports, given to Richard Nixon in 1948, inspired the first-term Congressman to contact Chambers, setting in motion the chain of events that would eventually lead to Hiss being jailed for perjury.

“George Crosley”

According to Alger Hiss, “George Crosley” was the pseudonym Whittaker Chambers used when they met. Chambers told HUAC he had never used the name, but at the trials in 1949, Chambers conceded he might have done so. For more information about two people who backed Hiss’s recollections on the issue, see the entries for Samuel Roth and Claudie Catlett.

According to Chambers, Hiss knew him as “Carl” (no last name), one of the many pseudonyms Chambers acknowledged using. Other known Chambers aliases included: Charles Adams, Bob, David Breen, Lloyd Cantwell, David Chambers, Arthur Dwyer, Hugh Jones, John Kelly, Harold Phillips and Charles Whittaker.

Claude Cross

Cross served as Hiss’s attorney at his second trial. Cross was chosen because the defense believed its motion to move the second trial to Vermont might succeed, and the bookish Cross might appeal more to New England jurors than the bombastic Lloyd Paul Stryker, who had represented Hiss in his first trial. The defense was wrong on both counts. Its motion to move the trial failed, and although Cross was more adept at dealing with the documentary evidence than Stryker, he was not an effective advocate before the jury. Still, Cross demonstrated that a number of the State Department documents that Hiss allegedly gave to Whittaker Chambers had never been sent to his office.

Charles F. Darlington

Julian Wadleigh’s boss in the Trade Agreements section of the State Department, Darlington testified that Wadleigh (who had admitted giving documents to Whittaker Chambers) had a “well-developed curiosity.” He said he had frequently returned from lunch to discover Wadleigh at his (Darlington’s) desk reading through his papers. He also testified that when he visited Francis Sayre’s office, Sayre’s door was often closed, while Hiss’s was open. He said he had frequently seen Wadleigh in Sayre’s office.

John F. Davis

Davis was a Washington, D.C. lawyer who was hired by Alger Hiss to investigate Whittaker Chambers’ charges during the initial phases of the case before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

John W. Davis

John Davis was a former Democratic nominee for president (he lost to Calvin Coolidge in 1924) and a trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace when Hiss served as president. He testified as a character witness for the defense.

Lucy Elliott Davis

Lucy Davis was the proprietor of Bleak House in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where Whittaker Chambers said he had stayed with the Hisses in August 1937. She testified that she always had guests sign the register, which was produced at trial. Neither the Hisses nor the Chambers were listed in the register, and there was also no combination of two men and a woman during that period. Only three people had registered prior to that weekend, and Mrs. Davis was able to recall them accurately.

Donald Doud

A document examiner hired by the defense for its motion for a new trial, Doud lent credence to the defense’s theory that the Baltimore Documents were forgeries when he examined a series of letters typed on a Woodstock machine in 1929 by employees of the Fansler-Martin insurance firm. This machine was later given to Priscilla Hiss, Thomas Fansler’s daughter. Doud said the machine that typed the letters was manufactured sometime between 1926 and 1928. If this was correct, Woodstock #230,099, which was placed in evidence by the defense as the typewriter formerly owned by the Hisses, could not have been the Hiss machine because it was not manufactured until 1929, according to Woodstock company records.

For more on the typewriter, click here.

Laurence Duggan

Laurence Duggan

A high-ranking State Department official, where he served as Adviser on Latin American Affairs, and a friend of Alger Hiss, Duggan was the subject of a vague accusation by Whittaker Chambers during his 1939 conversation with Adolf A. Berle. (Berle’s notes only say “Duggan – cp?”)

Chambers’ friend Isaac Don Levine testified before HUAC on December 8, 1948 that Chambers at the 1939 meeting had told Berle that Duggan had passed on classified information. Berle denied this. (Levine said the same thing about Hiss, another assertion denied by Berle.) Less than two weeks later, Duggan fell out of a window and died (the New York police concluded there was no evidence of suicide or murder). Immediately after Duggan’s death, HUAC released Levine’s previously classified testimony, and committee member Karl Mundt said the Committee would release names of others “as they jump out of windows.” To quell the uproar that resulted from that comment, Richard Nixon, another Committee member, Mundt, and the U.S. Attorney General all declared that there was no evidence of espionage against Duggan.

Duggan had been interviewed by the FBI on December 10, 1948. He told them he knew Hiss but had no reason to suspect he was a communist. Duggan said in 1937 or 1938 he had been approached by Henry Collins to do some work on behalf of the communists but had refused, and the matter was dropped.

In 2002, retired KGB General Vitaly Pavlov said that Duggan had had occasional and reluctant contacts with Soviet foreign intelligence in the 1930s, withdrawing after the Moscow purge trials began. According to the Vassiliev Notebooks, Duggan (who had been given the codename “19th”) was approached again during World War II, but as one Soviet rezident reported back to Moscow in 1944, “It is absolutely obvious that ‘19th,’ frightened once in the past, does not want to become our agent.”

John Foster Dulles

The Secretary of State under President Eisenhower, Dulles was chairman of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace when Alger Hiss was its president in 1947-1948. Dulles asked Hiss to consider becoming president of the organization in January 1946, but his relations with Hiss chilled after Chambers’ accusations became public.

During the HUAC hearings in August 1948, Richard Nixon and HUAC leaked testimony and other information to Dulles about Whittaker Chambers’ charges. At that point, Dulles (who had been mentioned as a potential Secretary of State, had Thomas E. Dewey defeated President Truman in the 1948 presidential election) pressured Hiss to resign from the Endowment. Dulles later appeared as a prosecution witness at the trials, disputing Hiss’s recollection of the circumstances surrounding his resignation.

Evelyn Ehrlich

An expert in the detection of typographic and other forgeries who was associated with the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, Ehrlich was asked to analyze the typewriter evidence for Alger Hiss’s motion for a new trial. Ehrlich filed an affidavit with photographs showing clear differences in typefaces between the Woodstock machine #230,099 and the machine which typed the “Hiss Standards,” the personal documents acknowledged to have been typed on the Hiss’s typewriter in the 1930s. She also said that using the standards applied at trial by the FBI document examiner, Ramos Feehan, one could not tell the difference between the typing produced by the machine specially built by the Hiss defense for the motion for a new trial and the Hiss Standards — thus suggesting that forgery by typewriter was possible.

Thomas Fansler

Fansler was Priscilla Hiss‘s father. His insurance firm owned a Woodstock office typewriter, which he later gave to the Hisses. Questions remain to this day about whether the typewriter he gave them was the same Woodstock as Woodstock serial #230,099, which the defense found and placed in evidence. For more on the mystery surrounding the Woodstock typewriter, click here.

Edwin H. Fearon

Fearon was a document examiner hired by the defense before the first trial. Fearon’s examination led him to believe that Woodstock #230,099, which the defense would put in evidence as the typewriter once belonging to the Hisses, had typed the Baltimore Documents.

Fearon also said, however, that the Baltimore Documents had been typed on a 1928 Woodstock. Woodstock company documents revealed to the defense for its motion for a new trial indicated that #230,099 could not have been manufactured before July 1929.

For more on the typewriter, click here.

Ramos C. Feehan

Feehan was an FBI document examiner. He was a crucial witness before the grand jury in December 1948, when he testified that the same machine used by Priscilla Hiss to type personal correspondence (of which they had obtained samples) had also typed the copies of the State Department documents that Whittaker Chambers said he had received from Hiss for transmission to Moscow. Soon after hearing his testimony, the grand jury voted to indict Hiss for perjury when he denied having given Chambers any government documents.

Feehan repeated his testimony at both trials and was not challenged by the defense, which insisted that the typewriter was out of the Hiss’s home by the date that appeared on the State Department documents. After Hiss’s conviction, his attorney, Chester Lane, began to gather evidence to impeach Feehan’s testimony. Unknown to the defense, Feehan, after the first trial, conducted a test to see whether the typewriter found by the defense, Woodstock #230,099, had actually typed the State Department documents. Feehan concluded that it had, despite the fact that FBI field agents had already gathered information suggesting that #230,099 was manufactured too late to have been Hiss’s machine. Feehan did not testify about his findings at the second trial.

Noel Field

Noel Field

Field was a former colleague of Alger Hiss’s. His name was brought into the case most prominently by Hede Massing. In recent years, Hiss’s detractors have pointed out that in the early 1950s, when Field was imprisoned in Hungary for espionage, he implicated Hiss. Others note that Field was being tortured and held in solitary confinement at the time and was telling his captors anything they might want to hear.

After his release from prison in the mid-1950s, Field sent Hiss a note reaffirming his belief in Hiss’s innocence, saying, “I need hardly tell you how angered and outraged I was over the irresponsible allegations made against you. Your testimony fully harmonizes with the memory I had of you during our all-too-brief acquaintance in Washington.”

For more on this issue, click here to read Ethan Klingsberg’s article in The Nation.

Plum Fountain

A woman whose nickname was the source of some amusement at the trial, Fountain’s married name was actually Olivia Tesone.

When offering evidence of his close relationship with the Hisses, Whittaker Chambers said he had met a friend of theirs named Plum Fountain while dining with them at a restaurant in Georgetown. Ms. Fountain testified for the defense at the second trial. She said that during her friendship with the Hisses, she had never met them at a restaurant in Georgetown, nor had she ever met Chambers.

William Reed Fowler

Fowler was married to a housekeeper in a building in Baltimore where Whittaker Chambers once lived. Chambers claimed to have hired Edith Murray as a maid when he lived in the building (she testified that she had seen Chambers and Hiss together). In an affidavit filed for Hiss’s motion for a new trial, Fowler said he had visited the building frequently and recognized the Chambers family. He said they didn’t have a maid at that time. Fowler’s ex-wife filed an affidavit for the government, saying that she and Fowler had not been frequent visitors to the building.

Felix Frankfurter

Alger Hiss’s mentor at Harvard Law School, Frankfurter would go on to be an honored member of the US Supreme Court. Upon Hiss’s graduation from Harvard, Frankfurter selected him to become secretary to the aging Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes. In 1933, he encouraged Hiss to join the New Deal.

Frankfurter would appear as a character witness for Hiss, but when the guilty verdict was appealed to the Supreme Court, Frankfurter and Justice Stanley Reed (who had also testified for Hiss) had to disqualify themselves. As a result, Hiss’s appeal was turned down (it came up two votes shy). Justice William O. Douglas later wrote that, if the case had been reviewed, “…in my view no Court at any time could possibly have sustained the conviction.”

Henry W. Goddard

The judge in the second Hiss trial was a Republican appointed to the bench by President Warren G. Harding in the early 1920s. Goddard was criticized by Alger Hiss and his attorneys for a series of rulings they said were unfair to the defense. He allowed the testimony of Edith Murray, Chambers’ alleged maid, as a rebuttal witness at the end of the trial instead of as a direct witness, which prevented the defense from preparing an effective cross examination. He also allowed Hede Massing to testify after Judge Samuel Kaufman barred her from the first trial.

According to Tony Hiss’s Laughing Last, Goddard napped frequently during the trial. Goddard seated the vocal conservative Alice Longworth Roosevelt (President Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter) and her niece directly in front of the jury. The pair made a practice of smiling and nodding their heads whenever the prosecutor would make a point and frowning when defense attorneys made theirs.

In 1952, Goddard denied the defense’s motion for a new trial, not even allowing a hearing on the matter, despite a huge amount of new evidence turned up by the Hiss team after his conviction.

Donald Hiss

Alger Hiss’s younger brother, Donald Hiss was also alleged by Whittaker Chambers to have been a member of the communist underground. Donald Hiss denied the charges before HUAC and later testified for the defense at both trials. He was never indicted or prosecuted for asserting his own or his brother’s innocence.

Like his brother, Donald Hiss was a New Dealer. He, too, served as a secretary to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. During the New Deal, Donald Hiss served in both the Labor Department and the State Department, where he worked directly under Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson. In later years, Hiss was a partner at Covington & Burling, the Washington, D.C. law firm where Acheson also became a partner after leaving the government. Although they followed him for years, by 1952 the FBI had essentially cleared Donald Hiss of all the charges that Chambers had leveled against him.

Priscilla Hiss

Alger Hiss’s wife was said by Whittaker Chambers to have typed copies of State Department documents brought home from work by her husband for eventual transmission to the Soviets. Until her death, Mrs. Hiss steadfastly maintained that she and her husband were innocent of all charges. When Allen Weinstein’s Perjury was first released in galley form, it contained a passage that reportedly quoted Mrs. Hiss confessing her husband’s guilt at a dinner party in 1968. Mrs. Hiss protested sharply, and Weinstein deleted the story. For more about this incident, click here.

A Bryn Mawr graduate and a grade school English teacher at New York’s Dalton School when the Hiss case began, Mrs. Hiss had a hard time finding work after her husband went to jail. She eventually landed a job in the basement of a Doubleday Book Shop – the management didn’t want her face seen by customers. In later years, she worked in an art gallery and in publishing. After the Hisses separated in 1959, she became active in local reform Democratic politics in Greenwich Village, serving on the executive board of the Village Independent Democrats, the club from which Mayor Ed Koch emerged. Toward the end of her life, Priscilla Hiss was appointed to Manhattan’s Community Planning Board No. 2 by Borough President Percy Sutton.

Timothy Hobson

Priscilla Hiss’s son by her first husband, Thayer Hobson, Tim Hobson, who was born in 1926, was raised by the Hisses and moved with them to Washington in 1933.

In 1948, Whittaker Chambers was asked by HUAC to provide details about his knowledge of the Hiss family in the 1930s. Chambers did so on August 7, 1948. Many of the details he offered were wrong. Chambers described young Tim inaccurately as a “puny, nervous little boy.” He also incorrectly described Tim’s schooling (see the entry for Thayer Hobson).

Chambers said that he visited the Hiss household every week in 1937 (which the Hisses denied), beginning early that year. At that time, Hobson had just been run over by a car and was subsequently confined to bed for weeks. Chambers did not mention this near-fatal accident and injury to any of the investigators. (When the Hisses’ former maid, Martha Pope, was questioned by the FBI, she remembered Hobson’s accident in great detail.)

In 1949, as Hiss was preparing for trial, Hobson, then 22, said he would testify that Chambers did not visit the house in 1937. He would also have testified that Alger Hiss did not bring home State Department documents, and that Priscilla Hiss did not type copies of the documents that Alger Hiss did not bring home. The FBI interviewed Hobson, who would later say that his interview amounted to “blackmail.”

After his stepfather went to jail, Hobson decided to become a doctor. He put himself through pre-med courses at New York University by working nights as an orderly at Bellevue Hospital. A Navy discharge made it difficult for Hobson to get admitted to an American medical school, so he learned French in a single summer and enrolled at a Swiss medical school in Geneva. He was later an intern, and Chief Surgical Resident, at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco. Hobson married, had four children, and practiced medicine in California and Wyoming. Now retired, divorced, and residing in the Bay Area, Hobson is the last living eyewitness to the events of the Hiss case.

Click for a transcript of a an extensive 2002 conversation with Hobson and a video of a talk given by Hobson at NYU.

Thayer Hobson

Priscilla Hiss’s first husband and Tim Hobson’s father, Thayer Hobson was a New York publisher (the head of William Morrow).

Before HUAC, Chambers said Hobson was paying for Tim’s education, but that the Hisses were putting Tim in less expensive schools and diverting the difference in tuition to the Communist Party. Thayer Hobson attested to the fact that Tim Hobson was moved to a succession of more expensive schools, and that he paid his son’s school bills directly.

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

A colorful and compassionate man, Justice Holmes remains one of the most revered members of the U.S. Supreme Court. Alger Hiss served as his secretary for a year after graduating from Harvard Law School.

Donald Hiss also served as Holmes’s secretary. They were the only two brothers to share this distinction.

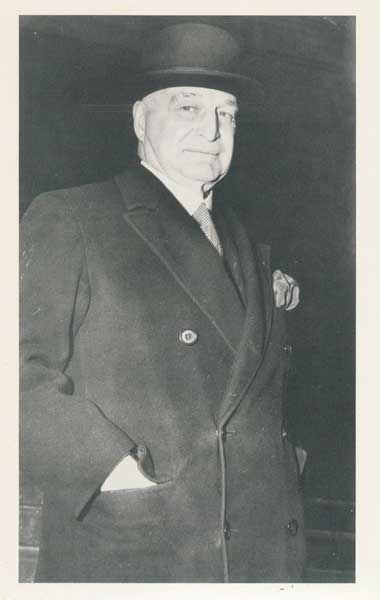

J. Edgar Hoover

J. Edgar Hoover

The founding director of the FBI and head of the organization during the time of the Alger Hiss investigation, Hoover was one of the most powerful men in Washingtion for nearly half a century. Documents released under the Freedom of Information Act indicate that Hoover personally directed his agents to ensure Hiss’s conviction. Tens of thousands of pages of FBI files have been released but often with significant deletions. Considerable information continues to be withheld from the public.

Stanley K. Hornbeck

During World War II Hornbeck was the Political Adviser for Far Eastern Affairs in the State Department, and for a while he was Alger Hiss’s boss. A number of the documents introduced at the trials were alleged by Chambers to have come from Hornbeck’s office. By pointing out the routing stamps on them and combing the State Department’s own distribution lists, the defense was able to show that they had never crossed Hiss’s desk.

Felix Inslerman

Inslerman was allegedly one of the photographers of State Department documents given to Whittaker Chambers by Alger Hiss. Originally identified only as “Felix,” Inslerman was not the first photographer Chambers identified as “Felix.” (That man was Samuel Pelovitz.) Inslerman appeared before the grand jury, as did as his wife. He refused to answer questions regarding Chambers both then and at Hiss’s trials. Under considerable pressure, Inslerman finally told his story to Joseph R. McCarthy’s Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security in 1954. Although he then admitted to having worked with Chambers, his testimony conflicted with Chambers’ account on a number of key points.

Inslerman’s name turns up in the Vassiliev Notebooks in garbled form; it is known that, although not formally a Communist, he visited Moscow in 1935 using a passport issued in the name of Frank DeLac, and that while there was taught to photograph documents and cipher messages.

Matthew Josephson

Matthew Josephson

One of America’s most respected biographers and reporters and author of The Robber Barons, Josephson was working on a book on the Hiss case when he died in 1978. His memoir, Infidel in the Temple, contains an account of meeting Chambers in the 1930s when the two nearly came to blows over what he characterized as Chambers’ bizarre behavior.

In two letters reproduced on this site, Josephson wrote of the warmth between Alger Hiss and his friends.

Samuel H. Kaufman

Samuel H. Kaufman

The judge presiding over the first Hiss trial, Kaufman was removed after the trial when Richard Nixon and other conservatives called for his impeachment, saying he had acted improperly by exluding the testimony of Hede Massing.

Years later, Kaufman told a friend of Hiss’s, “You and I both know that man is innocent.”

J. Kellogg-Smith

Kellogg-Smith was the owner of a summer camp in Chestertown, Maryland, where Timothy Hobson spent the summer of 1937. Chambers had claimed he and the Hisses had taken a trip to Peterborough, New Hampshire that August, but Hiss said he had spent that time with Hobson. At the first trial, Kellogg-Smith testified for the defense that this was true. At the second trial, his testimony was buttressed by his wife Margaret, who also recalled seeing the Hisses at the camp when they were said by Chambers to have been in Peterborough. For more on this controversy, see Lucy Elliott Davis.

Alfred Kohlberg

A wealthy businessman with dealings in China, Kohlberg financed Isaac Don Levine‘s anti-communist magazine, Plain Talk. With Levine as a source, Kohlberg spread rumors about Hiss, specifically to John Foster Dulles, Hiss’s boss at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Chester Lane

Chester Lane headed the legal team that put together the motion for a new trial in 1952, two years after Alger Hiss’s conviction. Despite Judge Goddard’s refusal to give him subpoena power to get typewriter records, Lane was able to cast doubt on, among other things, the Woodstock typewriter placed in evidence by the defense (implying it may have been a deliberate plant); Whittaker Chambers’ amended story that he left the Communist Party in 1938; and the likelihood that the State Department documents were typed when Chambers had said they were. Judge Goddard refused to grant a hearing on the motion.

Myles J. Lane

Myles J. Lane was the Assistant U.S. Attorney who opposed Hiss’s motion for a new trial in 1952.

Louis Leisman

Leisman was the janitor in a building where Whittaker Chambers and his family lived in Baltimore. Leisman gave the defense an affidavit for its motion for a new trial, casting doubt on Chambers’ claim that he had employed Edith Murray as a maid in his building. Leisman said he knew all the tenants in the building and that none of them employed a maid. The government tried to undermine Leisman’s credibility, claiming he was an alcoholic and an irresponsible drifter. Leisman complained of harassment by the FBI after he filed his affidavit.

Isaac Don Levine

Isaac Don Levine

The influential anti-communist editor of Plain Talk magazine, Levine took Whittaker Chambers to see Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle in 1939 to inform him about communist activities in Washington. Chambers mentioned the names of Alger and Donald Hiss at the meeting, and this set in motion a chain of events that would lead to the Hiss case.

Many years later, Levine told author Meyer Zeligs that Chambers had come to him in 1938, saying he needed money and was looking to sell what Levine said was a vague magazine article about communist activities in the United States. Levine subsequently worked with Chambers to help develop his story.

Nathan I. Levine

The nephew of Esther Chambers; it was in a dumbwaiter in his Brooklyn apartment that an envelope was stored allegedly containing the film and documents that would later be used as evidence against Alger Hiss. Chambers said he had given the papers to Levine in 1938, telling him to hold them as a “life preserver” in the event his life was threatened by communist agents. Chambers later testified that though the contents of the envelope might have been his only protection against a murder attempt, for many years he forgot that the envelope existed. Levine testified that he never saw the contents of the envelope.

In November 1948, Chambers said he remembered the envelope after he was asked by Hiss’s attorney to provide documentary evidence to support his charges against Hiss. The defense later had a document examiner, Daniel Norman, analyze the envelope. His report stated that many of the papers could not have been kept inside the envelope for 10 years.

Ira Lockey

Lockey, a moving man, was given a Woodstock typewriter after performing a moving job for a man named Vernon Marlow. Thinking this was the same typewriter that the Hisses had once owned and given to the Catlett family, the defense bought the typewriter from Lockey in 1949. As it turned out, Woodstock #230,099, which was then offered in evidence by the defense, was not their machine. Click here to read more about the Woodstock typewriter.

Elizabeth McCarthy

The official document examiner for the Boston and Massachusetts State Police, McCarthy gave an affidavit supporting the defense’s motion for a new trial. She said that, based on her examination, several different ribbons were used to type the document copies placed in evidence. This lent credence to the theory that several people, and not Priscilla Hiss, had typed the documents. McCarthy also compared the typing of the documents to samples of Mrs. Hiss’s typing and noticed clear differences between the two. As a result, she stated that Mrs. Hiss could not have typed the documents in evidence. Had this been known at trial, it would have counter-balanced the testimony of the FBI’s typing expert, Ramos Feehan.

Edward C. McLean

A classmate of Alger Hiss’s at Harvard Law School, McLean helped prepare Hiss’s defense at both trials. He later became a federal district judge.

John McDowell

McDowell was a conservative member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (R-Pennsylania) and a former newspaperman. He played a prominent role in the questioning of Alger Hiss in August 1948. Hiss’s answer to McDowell’s question about whether he had ever seen a prothonotary warbler convinced many people that Hiss was lying about his relationship with Whittaker Chambers.

McDowell would also figure into the controversy surrounding the Woodstock typewriter, when he said, in a letter written to a constituent in 1956, that the FBI had found the typewriter in 1948. This statement, along with others, has fueled speculation that the Woodstock typewriter found by the defense and produced at trial was actually planted by the FBI McDowell was defeated in a reelection bid in 1948.

Benjamin Mandel

Mandel, HUAC’s head of research, was a former Communist who allegedly issued Whittaker Chambers’ Communist Party card. During the HUAC hearings on August 7, 1948, Mandel showed Chambers a photograph of Alger Hiss listening to someone ask him a question from a distance. In the picture, Hiss had his hand cupped to his ear. Chambers responded by saying that Hiss was deaf in one ear. This was taken by the committee as more evidence of the closeness of Hiss and Chambers. Hiss, in fact, had normal hearing in both ears.

To listen to Hiss recall this incident, visit our audio archive. See also Malcolm Cowley.

William Marbury

A prominent Baltimore lawyer and a boyhood friend of Alger Hiss, Marbury served as Hiss’s attorney in the libel suit phase of the case. Marbury’s request to Whittaker Chambers during pre-trial depositions to produce documentary evidence in support of his allegations against Hiss led Chambers to the dumbwaiter in Nathan Levine‘s apartment. Chambers claimed that, a decade before, he had put the evidence in an envelope and given it to Levine, who had placed it in the dumbwaiter.

Marbury’s questioning of Chambers also produced a fuller picture of Chambers’ account of his days in the communist underground – as well as the numerous inconsistencies in his story– than he had revealed to HUAC. William A. Reuben wrote more about this episode in his unpublished book, The Crimes of Alger Hiss.

Hede Massing

Hede Massing

Hede Massing was a self-confessed former communist, who was called by the prosecution to testify at the first trial to bolster Whittaker Chambers’ charge that Alger Hiss had been a communust. Massing’s testimony was excluded by Judge Samuel H. Kaufman, who ruled that her story was irrelevant to the charges against Hiss. At the second trial, however, Judge Henry W. Goddard permitted Massing to testify. Massing told the second jury that in 1935 she had met Hiss at a party held at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Noel Field, whom she described as intimate friends of hers, and that at the party she and Hiss had bantered about their competition to enlist Noel Field, a State Department official who specialized in arms reduction negotiations, into their respective Communist underground groups. For his part, Hiss said he had never met Massing.

Massing, who appears in the Vassiliev Notebooks under the covername “Redhead,” tells the same dinner party story there, though dating it a year later. The story, however, is an impossibility either way, because on both occasions Noel Field was in London as part of the U.S. delegation to successive Naval Limitation Conferences.

Karl E. Mundt

A Republican member of HUAC from South Dakota and an outspoken critic of the New Deal, Mundt later became a U.S. Senator.

Thomas F. Murphy

Murphy, an Assistant U.S. Attorney, was thrust into the national spotlight when he became the prosecutor in both Hiss trials. After the second trial conviction, Murphy was appointed first as Police Commissioner of New York City and later to the federal bench.

Hiss’s coram nobis petition, filed in 1978, documented numerous examples of prosecutorial misconduct by Murphy and his staff.

Edith Murray

According to Whittaker Chambers, Edith Murray was, for a while, his family’s maid. She was a surprise rebuttal witness for the prosecution at the end of the second trial. Murray testified that she had seen the Hisses and the Chambers together at the Chambers’ apartment in Baltimore. In Hiss’s motion for a new trial, the defense turned up two people, William Reed Fowler and Louis Leisman, who claimed Chambers never had a maid in the building where Murray claimed she worked.

Hiss’s coram nobis petition contained FBI documents which showed that Murray could identify Alger Hiss only with help from the FBI and from Chambers. (She spent an afternoon at the Chambers’ farm before she made the identificaton at trial.) Her first comment, when shown a photo of the Hisses, was that they looked like people she had seen in the movies. She testified that the FBI never told her that the picture she was shown was of the Hisses. In an FBI document obtained in 1975, however, Murray says in a signed statement, “The agents have shown me a photograph of a person they have told me is Alger Hiss, and the person looks something like the slender man who accompanied the Lady from Washington on the above mentioned visit to the Cantwells [Chambers].” This was unlike the definitive identification she offered in court.

Dr. Henry A. Murray

Dr. Murray was a psychiatrist who testified for the defense at the second trial. He supported the testimony of another psychiatrist, Carl Binger, who said that Chambers was psychopathic and misrepresented the truth.

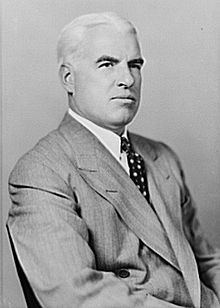

Richard M. Nixon

Richard M. Nixon

At the time the Hiss case broke, Richard Nixon was a first-term Republican Congressman from California and a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was Nixon who pursued Whittaker Chambers’ story when other members of HUAC seemed ready to drop the matter after Hiss’s impressive appearance before the committee in early August, 1948.

Nixon’s questionable behavior in 1948 included colluding with Chambers; leaking secret HUAC testimony; and offering knowingly misleading testimony to the Hiss case grand jury.

Over the years, Nixon would be quoted on a number of occasions as having said that he and his associates either built or found the Woodstock typewriter, which was placed in evidence by the defense. Nixon’s statements have raised continuing questions about whether the typewriter was planted and the evidence against Hiss forged.

Nixon was elected to the United States Senate in 1950. He was twice elected vice president of the United States (in 1952 and 1956) and was twice elected president (in 1968 and 1972). In 1974, shortly before his expected impeachment by the House of Representatives for his illegal actions that led to the Watergate scandal, he became the first president to resign the office.

Daniel Norman

A document examiner hired by the defense for its motion for a new trial, Dr. Norman took test samples of the Baltimore Documents and the envelope in which Chambers said they had been stored. He found that the documents were of different ages. Nor were they typed with the same ribbon, he said. This led the defense to conclude that they were typed in different years (not over a single period of days in 1938, as Chambers claimed). Norman also noted significant differences in paper sizes among the documents, and pointed out that some pages were cut to make them all appear to be the same size. Hiss’s attorney, Chester Lane, said this was further indication of a forgery, because an espionage agent would not take the time to make such adjustments.

Dr. Norman also examined the envelope and found that stains that had leaked through the envelope were not found on the pages. Norman maintained that if the envelope had been stored with the documents inside for ten years, at least some of the stains would have been evident on the paper inside the envelope.

Dr. Norman also analyzed the Woodstock typewriter #230,099, found by the defense and thought to be the old Hiss family typewriter. He saw that the typebars on the machine had been crudely altered with blobs of solder that were still present on the keys. He said none of this work matched the kind of manufacturing techniques used in the Woodstock factory, leading to his conclusion that the machine had been altered.

Gerald Nye

Nye was a Republican Senator from North Dakota and the chairman of a Senate committee charged with investigating the activities of the munitions industry during World War I. In 1934 and 1935, Alger Hiss was a counsel to this committee. It was in this capacity that he said he met and helped a freelance writer named George Crosley, who would later turn out to be Whittaker Chambers.

Samuel J. Pelovitz

Pelovitz was a Baltimore printer who became part of the Hiss case when Whittaker Chambers identified him to the FBI and to the grand jury as “Felix,” the photographer who had photographed the documents taken from the State Department (allegedly by Alger Hiss). Pelovitz testified to the grand jury that he was not living in the Baltimore area when he was supposed to have photographed the documents. With the help of the FBI, Chambers subsequently identified Felix Inslerman as the photographer. Click here to read Inslerman’s testimony.

None of the Pelovitz material was publicly known until 1999, when the grand jury minutes were released. The defense never learned that Chambers had repeatedly misidentified a man with whom he had allegedly met weekly for more than six months.

Jozsef Peter

Peter, who also used the covername J. Peters, was a Ukrainian-born U.S. Communist Party official whose real name was Sándor Goldberger (and who according to the Vassiliev Notebooks also had the pseudonyms “Steve” and “Storm”). According to Whittaker Chambers, Peter set up the communist underground in the United States. Peter discussed Chambers’ allegations in an excerpted portion of his memoirs. Peter emigrated to the U.S. in 1924, and left for Hungary in 1949 in order to avoid deportation. In 1935, Peter published a book, The Manual of Organization, about creating a CPUSA underground, but his actual roles and responsibilities remain unclear. Although Peter appears frequently in Vassiliev’s notes, a 1943 memo in the Notebooks makes it clear that he was not interested in collecting intelligence information.

William Ward Pigman

Pigman, an engineer with a doctorate in biochemistry who was known for his work in complex carbohydrates and in enzymes (he was later chair of the biochemistry department at New York Medical College), worked in the 1930s for the National Bureau of Standards, an agency which was the source of a number of government documents contained in the “Pumpkin Papers,” material that Whittaker Chambers said had been given to him for transmission to Moscow.

When the complete contents of the “Pumpkin Papers” were finally unsealed in the 1970s, it was found that those documents obtained from the Bureau of Standards consisted of Navy Department pamphlets and hand-outs that, even when collected, had always been publicly available. (They covered subjects such the color recommended for painting government fire extinguishers.) This was information that would have been of no interest to the Soviet Union or practically anyone else.

Testifying in December 1948 before the Hiss case grand jury, Pigman denied handing any documents over to Chambers, saying he had never met him. Although Pigman’s name is mentioned in the Vassiliev Notebooks (with the covername “114th”), he denied having been a member of the Communist Party or having had any association with it, describing himself as a moderate Democrat.

When they were unsealed in 1999, the grand jury minutes showed that Pigman was repeatedly threatened by prosecutors with perjury charges, but he maintained his story and was not indicted.

Lee Pressman

Pressman was a classmate of Alger Hiss’s at Harvard Law School and his colleague in the Agricultural Adjustment Administration in the early days of the New Deal. Whittaker Chambers said Hiss and Pressman were members of the same communist underground study group in Washington during the 1930s, the so-called “Ware Group.”

Pressman stayed quiet until 1950, when he waived his rights and agreed to testify before HUAC. Before the committee, Pressman acknowledged the existence of the underground group and admitted having been a member for a year. He stated that Hiss had not been a member of this group at any time. His testimony was cited in Hiss’s motion for a new trial. The government responded with an affidavit from Nathaniel Weyl, saying Hiss had been a member. (No one else, including Chambers, had previously mentioned Weyl’s name in association with the group.)

After leaving the government, Lee Pressman, an eloquent lawyer, became general counsel of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (C.I.O.). He appears in the Vassiliev Notebooks in several places – under the covername “Vig” – where it is implied that Soviet foreign intelligence was still in contact with him in 1950.

John Rankin

John E. Rankin

Rankin, a former Ku Klux Klan member, was a powerful Democratic member of HUAC from Mississippi. According to historian David Caute, in his book, The Great Fear, Rankin called the Federal Fair Employment Practices Commission “communistic” and once proposed a bill that would fine teachers $10,000 and jail them for 10 years if they were found to “convey the impression of sympathy with the Communist ideology.”

In December 1948, Rankin read the contents of the Baltimore Documents into the Congressional Record. He then talked about “the American boys who were killed, who lost their lives as a result of this treason,” and also suggested that if the spy ring had been caught in time, “we might not have had a Pearl Harbor.”

William Remington

William Remington

The case of William Remington was one of the most tragic of the era. Remington, like Alger Hiss, denied espionage charges against him (in his case, by Elizabeth Bentley) and, like Hiss, sued for libel. The case was settled out of court for $10,000. Remington, who served the New Deal in several capacities, was cleared by the Loyalty Board. He also denied the charge before HUAC but was indicted by a grand jury whose foreman co-wrote Bentley’s autobiography. Remington was convicted, but the case was thrown out of court. At a second trial, he was again convicted of perjury. This time the verdict stood. While in the Lewisburg penitentiary (where Hiss was also jailed), Remington was killed by a mentally disturbed prisoner.

Franklin Victor Reno

Reno, a brilliant mathematician, worked for the government at the U.S. Army Proving Grounds in Aberdeen, Maryland. Reno had been a member of the Communist Party and had briefly known Whittaker Chambers, but by the time he was working for the Army he had cut himself off from communist activities. After Chambers himself left the Party, he visited Reno and asked him for money.

According to Meyer Zeligs, several of Reno’s co-workers considered this visit a form of blackmail and gave Reno the $50 that Chambers was demanding. They also said Chambers was threatening that if Reno didn’t turn over to him a document – any document – Chambers would expose Reno’s Communist past to authorities. Reno gave Chambers a document that had been casually discarded. Chambers later turned it over to the government as proof of his charges of espionage. The paper contained the firing tables of a 1917 Browning machine gun.

In 1951, Reno was indicted on charges of concealing his membership in the Communist Party from the government. He pleaded guilty and served three years in prison at Leavenworth. His name turns up in the Vassiliev Notebooks, where he is said to have had the covername “118th.”

William Rosen

Rosen’s name came up during the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in August 1948, when Whittaker Chambers claimed that Alger Hiss gave his 1928 Ford to a service station in Washington, DC that was owned by a member of the Communist Party. Chambers said that Hiss wanted the car to be used by a loyal Party worker. In subsequent testimony, Hiss claimed he had been unsuccessfully trying to get rid of the car, which he said was virtually worthless, when he gave it to Chambers as part of a deal to sublet an apartment to Chambers in 1935.

To support Chambers’ story, committee investigators turned up motor vehicle records which showed that Hiss had not purchased a new car to replace the Ford until September 1935, several months after Hiss had sublet his apartment to Chambers. That meant, they said, that Hiss would have left himself without a car if he had given the Ford to Chambers when he said he did. When Hiss refused to change his story, saying he did not have access to records which could sharpen his memory, committee members were openly scornful.

Additional records turned up by the committee showed that Hiss had transferred the car’s title to the Cherner Motor Company in Washington on July 23, 1936. That same day, according to the title, the car was transferred to a man named William Rosen and a chattel mortgage of $25 was placed on the car (supporting Hiss’s testimony that the car was worth very little).

Contrary to Chambers’ story, the Cherner Motor Company was not a service station, but rather the largest Ford agency in Washington. Subsequent investigations by the defense revealed that the company did not record the sale in its customary fashion, and records relating to the transfer of the car to Rosen were missing.

When Rosen was located, he said he had been expelled from the Party in 1929. He was subpoenaed to testify for the prosecution at the second Hiss trial. Claiming Fifth Amendement protections, he refused to answer most questions put to him. He did say, however, that he had never met Alger Hiss or J. Peters. He also said he was not in Washington when the transfer was made. An examination of the signature on the back of the transfer revealed it was not Rosen’s.

Samuel Roth

A New York publisher, Roth had once received submissions from “George Crosley,” a.k.a. Whittaker Chambers. At one point, Roth was the only independent person to back Hiss’s assertion that Chambers had used the name George Crosley – a claim that Chambers had at first denied. Roth was a publisher of erotic material, and the defense decided he would make a negative impression in court, so he was never called as a witness. Click here to read the affidavit Roth had given to the defense.

George Norman Roulhac

A rebuttal witness for the prosecution, Roulhac lived with the Catlett family for some time (Claudie Catlett was the Hisses’ maid) and testified that he did not see a typewriter at their home until about three months after he moved in. That would have placed the typewriter there in April 1938. His testimony buttressed the prosecution’s contention that the Hisses had their Woodstock typewriter during the period the documents were allegedly typed.

According to FBI documents released in 1975, Roulhac told the FBI he was not certain when he first saw the typewriter, and that it might have been in the Catletts’ possession before he moved into their home. He also said the typewriter was a small portable, one that did not resemble the large Woodstock office machine.

Roulhac testified that he had been in the federal court building three or four times, to meet with FBI representatives before the trial. According to a memorandum written by prosecutor Thomas Murphy that was part of the 1970s FOIA releases, Roulhac had met with the prosecutor almost every day for a month before the trial.

Francis B. Sayre

Francis B. Sayre

An Assistant Secretary of State during the Roosevelt administration and Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law, Sayre was Alger Hiss’s boss in the Far Eastern Division of the State Department. He testified for the defense at the second trial, saying that a number of the documents placed in evidence came not from his (and Hiss’s) office, as was asserted by Whittaker Chambers, but from a different section of the State Department, the Trade Agreements Division, where Julian Wadleigh – who admitted passing documents to Chambers – worked.

Sayre also testified before the grand jury in New York, but he had been out of the country and was unable to appear until after Hiss had been indicted. Nonetheless, Sayre made a strong defense of his former assistant. See the entry on Malcolm Cowley for more on Sayre.

Meyer Schapiro

Meyer Schapiro

Schapiro was a noted professor of art history at Columbia University in New York City, and Whittaker Chambers’ classmate and friend while the two were Columbia undergraduates. Schapiro figured prominently in two aspects of the case. Chambers testified that his Russian connection, Colonel Boris Bykov, gave him money to buy gifts for his Communist cohorts. Chambers said he had used the money to buy Bokhara rugs for them. Schapiro, not knowing anything about a Communist connection, purchased the rugs and arranged for their delivery. Schapiro supported this story at trial. (See also George Silverman).

Questions about Schapiro’s involvement and possible perjury in his testimony were raised in the 1970s by New York attorney Raymond Werchen, who compared the rug receipts signed by Mrs. Schapiro and the check signed by Mr. Schapiro, and concluded that the signatures were identical.

Schapiro also played a prominent role in Chambers’ break from the Party. When he first told the story, Chambers said that after he left the Party and went into hiding, he needed money and contacted Schapiro for help. Schapiro arranged for Chambers to do translation work for the Oxford University Press. For Hiss’s motion for a new trial, the defense used the company’s correspondance with Chambers to trace Oxford’s involvement with him, and found this connection had been established before the last date of the State Department documents allegedly collected from Alger Hiss. If Chambers was already in hiding at the time, he could not have gotten the documents from Hiss.

In response, Chambers then said he was only planning his departure when he got the translation work. According to documents released by the FBI in 1975 that were previously unknown to the defense, Schapiro continued to maintain that Chambers had contacted him for help only after leaving the Communist Party.

He gave similar testimony to the grand jury investigating espionage in 1948. The minutes of his testimony were not released until 1999.

Horace W. Schmahl

Schmahl was a private investigator for the defense before the first trial. FBI documents obtained in 1975 showed that Schmahl was meeting regularly with prosecutor Thomas Murphy and the FBI during this time, turning over information he had found along with regular working papers of the defense. For Schmahl to have worked as an FBI “mole” was a violation of Hiss’s Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial.

Harold Shapero

Shapero was an attorney and an assistant to Lloyd Paul Stryker for the defense at the first trial.

George Silverman

Silverman was an economist and government employee whose early experiences with Whittaker Chambers strikingly paralleled Alger Hiss’s version of his own acquaintance with Chambers. In the early 1930s, Silverman, who then worked for the Railroad Retirement Board in Washington D.C., met a freelance writer named “David Chambers” (Whittaker Chambers). Chambers told him he wanted to write about Silverman’s government work. Chambers was a charming companion, but at a series of lunch meetings began borrowing money from Silverman that he failed to pay back. Silverman told this story to the grand jury (he and Hiss were unaware of each other’s testimony). He also pointed to inconsistencies in Chambers’ story regarding a gift of rugs to Hiss, Harry Dexter White and himself.

Several deciphered “Venona” cables suggest that during World War II, Silverman (covername “Aileron”), who was then working for the Army Air Force, may have cooperated with Russian intelligence agents, although a 1944 memo by a Soviet rezident included in the Vassiliev Papers indicates that Silverman did not know “that he is working for us.”

Nathan Gregory Silvermaster

Known to the FBI as “Gregory” and in the Venona cables as “Pal,” Silvermaster was a government economist at the War Production Board during World War II who, according to Elizabeth Bentley, was the leader of a wartime group of government employees that collected information for the Soviets (the FBI’s 162-volume investigation into communist infiltration into the federal government is called the “Silvermaster File”). According to the Vassiliev Notebooks (where he also appears as “Pal”), Silvermaster in 1944 was awarded the Soviet Order of the Red Star. Silvermaster, who denied Bentley’s accusations, was never formally charged. After leaving government service he became a developer on Long Beach Island on the New Jersey coast, north of Atlantic City.

Herbert Solow

Solow, like Meyer Schapiro, was a classmate of Whittaker Chambers at Columbia University. He later became a journalist. In the late 1930s, Chambers asked Solow to help sell an article he had written about his Communist activities. According to Solow, Chambers was afraid for his life. Solow felt that Chambers’ fears were exaggerated and his article was vague, but he arranged a meeting between Chambers and Isaac Don Levine. Chambers told Levine he wanted to meet with President Roosevelt to share with him the information he had, but Levine was only able to set up a meeting between Chambers and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle, during which Chambers made his first charges against Alger Hiss and others.

William Spiegel

Spiegel was a Baltimore notions manufacturer who, according to Whittaker Chambers, loaned out his apartment to be used to photograph secret State Department documents that Chambers said he had received from Alger Hiss in early 1937. Spiegel testified before the grand jury in 1948 that he and his wife were not living in the apartment until the fall of 1937. They said the apartment was occasionally used by Chambers’ friend, David Carpenter, but that no photography work was done there. The defense never knew of the the testimony by William Spiegel and his wife Anna.

Edward R. Stettinius, Jr.

Considered one of the principal moving forces behind the creation of the United Nations, Stettinius in early life was a lawyer and industrialist who was named Chairman of U.S. Steel in 1938, at the age of 37. During World War II, Stettinius joined the Roosevelt administration.

He was named Secretary of State in 1944 and was also the head of the U.S. delegation to Yalta.

Robert E. Stripling

The chief investigator for HUAC on the Hiss case, Stripling interviewed Chambers a number of times in 1948. It was Stripling who, after speaking with Chambers in November 1948, ordered a subpoena issued for Chambers to turn over any evidence he had to HUAC. As a result, on December 2, Chambers gave committee investigators the film of government documents which would be called the “Pumpkin Papers.”

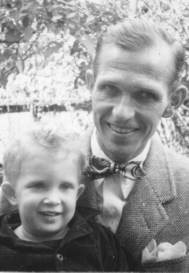

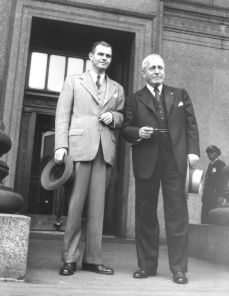

Lloyd Paul Stryker

Stryker, shown here with Alger Hiss, was known as the best criminal attorney in New York when he was hired to defend Hiss in the first trial. A man noted for his histrionic defenses, he lived up to his reputation as he ferociously attacked Whittaker Chambers’ testimony in court. His work helped earn a hung jury for Hiss.

Stryker told Hiss he could keep getting him hung juries until the end of time, but Hiss sought vindication. When Hiss thought the trial would be moved to Vermont, he replaced Stryker with the more sedate Claude Cross, a corporate lawyer from Boston who until then had never tried a criminal case.

J. Parnell Thomas

The chairman of HUAC in 1948, Thomas was a long-time opponent of the New Deal and a fierce anti-communist. In 1949, he was convicted of padding his expense accounts and accepting kickbacks, and served a prison sentence in a federal penitentiary.

Martin Tytell

Tytell was a typewriting and documentary expert hired by the defense for its motion for a new trial. After Alger Hiss claimed he was a victim of forgery by typewriter, his lawyers set out to test the theory that this could be done by building a typewriter that would match the typing on the “Hiss Standards,” the personal letters and documents acknowledged to have been written in the 1930s on the Hisses’ typewriter. Tytell was able to produce almost perfect copies of the standards. The defense’s theories about typewriter forgery had been ridiculed by the prosecution, but the British government had successfully used typewriter forgery during World War II. This remarkable story is recounted in detail in William Stevenson’s 1976 spy epic, A Man Called Intrepid.

Robert von Mehren

Von Mehren served as a defense attorney at both trials.

Henry Julian Wadleigh

Henry Julian Wadleigh

An economist who was a State Department official in the Trade Agreements division, where Alger Hiss also worked from 1936 to 1939, Wadleigh admitted to handing over hundreds of documents to Whittaker Chambers for use by Moscow. Wadleigh was not mentioned by Chambers as a source until after Chambers produced the so-called “Baltimore Documents” from his nephew Nathan Levine’s dumbwaiter in November 1948. The defense suggested that Wadleigh was the source of many of the documents offered at trial that Chambers claimed had come from Hiss, a possibility conceded by Wadleigh himself.

Wadleigh, who told the Hiss case grand jury that, although not a communist, he had agreed to “collaborate with the Communist Party” in 1935 because he had become alarmed by “the growing power of the Nazis in Germany,” was not charged with espionage since the statute of limitations had expired. Wadleigh appears in the Vassiliev Notebooks with the covername “104th.”

Harold Ware

Harold Ware

“Hal” Ware, an agricultural expert who, in the 1920s, had spent several years working on farming projects in the Soviet Union, and who, in the 1930s, worked for the New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Administration, was alleged by Whittaker Chambers to have organized the “Ware Group,” which Chambers called “an underground CP operation in Washington, D.C.” Ware died in a traffic accident in 1935. The testimony of Lee Pressman, who acknowledged having been a member of this group, describes its makeup and purposes in some detail. A 1944 memo included in the Vassiliev Notebooks stresses that the main members of the “Ware Group” “had never been GRU agents.”

Nathaniel Weyl

Weyl contradicted Lee Pressman‘s 1950 claim that Alger Hiss had not been a member of the Ware study group. Weyl asserted he himself had been a member, and so had Hiss.

Before Weyl told the Senate Internal Security Committee, in February 1952, about having belonged to the Ware group, no one else, including either Whittaker Chambers or Weyl’s own accounts, had linked Weyl to Ware.

In his book Treason, published in 1950, Weyl did not comment on the matter. When he testified before HUAC in 1943 he denied having been a member of the Communist Party.

Raymond Whearty

Whearty was the Assistant U.S. Attorney who, along with Thomas Donegan, led the grand jury sessions that resulted in the indictment of Alger Hiss on two counts of perjury.

Harry Dexter White

Harry Dexter White

White (1892-1948) is considered a founding father of the post-war global economic system, credited with creation of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. White, who held increasingly important positions in the Treasury Department during the New Deal, eventually becoming an assistant Secretary of the Treasury, and who in 1946 and 1947 was U.S. Executive Director of the IMF, appeared before HUAC on August 13, 1948 to rebut charges by Elizabeth Bentley that he had been a Soviet spy. During the hearing, White asked for time to rest, saying he had a weak heart. The committee denied this request; three days later White died of a heart attack at the age of 55.

Several years before White’s death, Whittaker Chambers named him as an underground communist contact, but did not accuse him of espionage. In November 1948, however, Chambers produced several sheets of yellow legal paper in White’s handwriting, saying they had been given to him by White ten years earlier (Chambers contended that he had stored in these pages in his nephew, Nathan Levine’s dumbwaiter along with documents received from Alger Hiss; these were the so-called “Baltimore Documents”). How these few notes of White’s actually came to Chambers has never been established.

After White’s death Chambers also claimed that, in 1937, he and Hiss had traveled to Peterborough, New Hampshire to visit White. Hiss’s attorneys cast doubt on this story, and on the witness stand Lucy Davis and J. Kellogg-Smith contradicted Chambers’ assertions about it.