The FBI Clears Donald Hiss

By Jeff Kisseloff

Donald Hiss and his one-year-old son Bosley, Washington D.C., 1942.

Alger Hiss was not the only Hiss accused by Whittaker Chambers of having had Communist Party ties in the 1930s. According to Chambers, Donald Hiss, Alger’s younger brother by two years, was both a Party member and active in the communist underground. Chambers, however, never charged Donald Hiss with espionage, and for that reason his accusations against Donald Hiss have never received the same level of attention and scrutiny as his more sensational charges against Alger Hiss.

But while the Donald Hiss-Chambers dispute has attracted only minor interest from most historians of the case, it is of major importance in assessing Chambers’ general accuracy as a witness, because it offers an independent opportunity to check his allegations against the factual record. Such an opportunity became generally available for the first time in 2005, when the FBI posted 354 pages from Donald Hiss’s FBI file on its Freedom of Information Act Reading Room Web page.

The Charges Against Donald Hiss

It must have seemed to Donald Hiss that he was forever traveling in his brother’s footsteps. He followed Alger both to Johns Hopkins University and to Harvard University Law School. He then succeeded his brother in the honor of serving for a year as secretary to Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Oddly, the one place where Donald Hiss actually preceded Alger was in the 1939 notes of Adolf Berle, the first written record of allegations by Whittaker Chambers about those he claimed had been active with him in the Communist Party. On September 1, 1939, Chambers and Isaac Don Levine, an anti-communist journalist, visited the home of Berle, who was then an Assistant Secretary of State. The penultimate entry of Berle’s notes of the conversation contains this reference:

Donald Hiss

(Phillippine Advisor)

Member of C.P. with Pressman & Witt –

Labor Dep’t. – Asst. to Frances Perkins –

Party wanted him there – to send him

as arbitrator in Bridges trial –

In subsequent interviews with the FBI and in testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, a federal grand jury in New York, and at Alger Hiss’s perjury trials in 1948 and 1949, Chambers repeated the substance of these charges – and in some instances amplified them. For example, before HUAC on August 7, 1948, Chambers said he had collected party dues from Donald, who knew him only as Carl. Regarding the Bridges case, he explained that when Donald was with the Labor Department in the late 1930s, the Communist Party wanted him to insert himself into a deportation case against Harry Bridges, a leftist, Australian-born labor leader on the West Coast docks. At that time, Chambers testified, Donald also had an opportunity to enter the State Department as legal adviser to the Philippine section. Chambers said the Party decided that Donald should go to the Phillippine s rather than work on the Bridges case, and that Donald, while he disagreed with the Party’s thinking, eventually submitted to Party discipline and took the State Department job.

In his own sworn testimony before two congressional committees (HUAC and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee), before the New York grand jury that indicted his brother, and at Alger Hiss’s second perjury trial, Donald Hiss, like his brother, specifically denied each of Chambers’ charges. He swore that he had never been a member of the Communist Party or the so-called Ware Group; that he had never met Chambers “by the name of Chambers, Carl or any other name”; and that the Party had nothing to do with his work for the Labor Department or for the Department of State.

“If I am lying,” Donald Hiss said forcefully before HUAC, “I should go to jail.” But unlike his brother, Donald Hiss was never indicted. In fact, after testifying on direct examination for the defense at his brother’s second perjury trial, he was barely cross-examined by prosecutor Thomas Murphy, who seemed unwilling to challenge his strong denials.

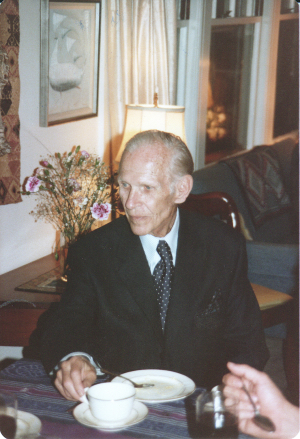

The FBI’s files on Donald Hiss, as well as evidence from the defense files, reveal why Murphy was hesitant to go after Donald Hiss: even the FBI didn’t believe Chambers’ story regarding him. Indeed, the head of the FBI’s Washington, D.C. field office wrote FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on January 29, 1952, after nearly a decade of FBI investigations, that Chambers’ allegations were “unsubstantiated.” He recommended that no more security investigations on Donald Hiss be conducted, and none were.

***

When asked by the grand jury on December 9, 1948 about his connection to the Bridges case, Donald Hiss testified that he was returning from a trip to the West Coast in September 1937, when he received a cable from his boss in the Labor Department, Solicitor General Gerard D. Reilly. Reilly wanted him to contact the Department, but because Hiss was then aboard a ship heading through the Canal Zone, he was unable to reach Reilly by phone.

It wasn’t until he arrived back in DC that they were finally able to connect. Reilly told him the Justice Department wanted him to investigate certain individuals who had given affidavits in the Bridges hearings, which had just gotten underway in California.

That November, Hiss was asked by Assistant Secretary of State Francis B. Sayre to join his staff. Hiss testified that Reilly tried to dissuade him, but to no avail. Hiss entered the State Department on February 1, 1938.

Two months later, Hiss recalled, Reilly got in touch with him, saying he was going to recommend to Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins that Hiss in effect be borrowed from the State Department to supervise upcoming hearings on the Bridges case. Hiss stated – contrary to what Chambers said – that he wasn’t eager to get involved in the case, telling Reilly that it was “an idiotic idea,” that he was 31 years old with no reputation as a lawyer, and that due to the tremendous publicity the case had already received, the department needed someone with a real reputation to oversee it. Hiss never did work on the case.

With an eye toward indicting Donald Hiss for perjury, the FBI investigated Hiss’s account “thoroughly,” according to one document. The key interview was conducted with Reilly on February 7, 1949. In that session, Reilly’s version of events surrounding the Bridges affair mirrored Hiss’s. He said it was his decision alone to ask Hiss to oversee the case – the Communist Party had nothing to do with it. FBI agents also examined Hiss’s personnel file and interviewed other officials with knowledge of the situation. Afterward, they concluded that Chambers’ allegations were no longer worth pursuing.

Despite the FBI’s findings, Allen Weinstein writes in Perjury that aspects of Hiss’s story are “extremely puzzling.” His analysis of Donald Hiss’s story asks three basic questions: 1) was Donald Hiss a communist?; 2) If not, then how did Chambers get his information about Hiss’s career?; 3) Was Chambers right about Hiss and the Bridges hearing?

Question one is clearly the most important because of its implications – not just for Donald Hiss’s credibility, but for Alger’s and Chambers’ as well. It’s curious that Weinstein never attempts to answer it directly. Instead, he’s content to merely imply a relationship by writing that “Chambers…proved well informed about the career of Hiss’s brother…”

But was Chambers that well informed? The above quotation is a direct reference to Berle’s notes. Chambers told Berle that Donald Hiss had been an assistant to Frances Perkins. He was wrong. Hiss never worked directly for her. Furthermore, labeling Hiss as a “Philippine advisor” is the kind of unsubstantive description that might have been obtained from a press release. It certainly is not indicative of the kind of personal relationship Chambers claimed to have had with Donald Hiss.

Moreover, Weinstein simply ignores Chambers’ subsequent statements to the FBI, which indicate he had very little personal knowledge about Donald Hiss. For example, a report of Chambers’s 1942 FBI interview says merely that “Miss Perkins thought a great deal of Hiss. The party planned to have Donald Hiss handle the Bridges case in Ca. in view of the influence he might have. After which time he went to the Phillppine division of the Department of State.”

In 1945, State Department Security Office Raymond Murphy reported about his interview with Chambers that Chambers could only trace the job of Donald Hiss and others to the end of 1937. This contradicts what Chambers would later say in 1948 and 1949, when he offered considerable post-1937 information about Donald Hiss, but had nothing to add in a more personal or professional way regarding Hiss. Nor was Chambers more forthcoming in his interview with the FBI a few months later when he simply identified Donald as Alger’s brother, without offering any additonal information.

In his second interview with Murphy in 1946, Chambers called Donald Hiss one of the leaders of the Washington underground, an allegation that he never repeated.

Instead of evaluating Chambers’s statements about Donald Hiss, Weinstein dwells on question two, the issues surrounding Hiss and the Bridges hearings (not a “trial,” as he calls them), asking why Perkins would have wanted Hiss to work on the hearings if he, as he claimed, had “never worked on the Bridges case.”

Second, if Hiss objected to the move, why did Perkins make a formal request that he work on the case in April 1938? The answer, Weinstein writes, is that “despite Donald Hiss’s denial,” he was considered the Department’s expert on the case. Weinstein’s sole source in support of that statement is a memorandum by Perkins from April 22, 1938. In it she requests that Hiss “be assigned to the case again. As you know, his transfer to the State Department was a source of serious concern to the legal staff here as he was the only member fully cognizant of the various aspects of this important immigration case.”

The letter, Weinstein claims, “contradicts Donald Hiss’s assertion that he was not involved with the Bridges case while at Labor.” But Weinstein is again chomping at the bit so eagerly to convict Hiss that he chooses to overlook other evidence that might explain the discrepancy.

For example, in the same defense files that Weinstein references, there is a 13-page memorandum of a conference with Donald Hiss’s boss, Gerald Reilly, on September 24, 1948. Reilly outlines a complete history of Donald Hiss’s work in the Labor Department. He also reveals in detail how and why Hiss was asked to work on the Bridges case. Reilly, who had no motivation to lie (and who told the same story to the FBI, where he could have gotten into legal trouble for lying), was in complete agreement with Donald Hiss. The decision to ask Hiss to work on the Bridges case was his and his alone. It wasn’t because Hiss had any specific knowledge or experience on the case, and he never did the work Reilly asked him to do. Reilly was the one who suggested to Perkins that Hiss work on the case, even after Hiss had moved to the State Department, but the request was made not because Hiss was any kind of expert on the case, as Weinstein states, but because the hearing was on the West Coast, and Donald Hiss happened to be on the West Coast then himself, on other labor Department business. It was a matter of convenience.

In a 1957 defense-file memo that Weinstein cites derisively in Perjury, Donald Hiss says he is mystified by Perkins’s letter, calling it “just verbiage.” Reilly’s memo appears to show that he’s correct. But there’s even more support for it, from an unlikely source – the FBI. In a document dated March 1, 1957, the Bureau says that it checked through Donald Hiss’s personal file at the Department of Labor and found nothing indicating he had ever worked on the Bridges case, much less had any expertise on it.

Contrary to what Chambers told Berle, while in the Department of Labor, Donald Hiss was never an assistant to Frances Perkins. He worked in the Office of the Solicitor as an assistant to Gerald D. Reilly.

Chambers said in his latter statements to the FBI that Donald Hiss did not want to go to the State Department, but eventually submitted to Party discipline and went. In his grand jury testimony, Donald Hiss stated the opposite –that he did want to go and had in fact been recruited by Assistant Secretary of State Francis B. Sayre, Jr.

Weinstein shows no indication of considering any of this. At the same time, he ignores the obvious: that Chambers’ faulty intelligence indicated only a cursory knowledge of Donald Hiss’s career as opposed to having gained the kind of accurate, inside information which would have come from the kind of friendship he claimed to have had.

Weinstein wants to know how Chambers got this information, if not from Donald Hiss. Weinstein suggests, without any evidence, that it came from Alger Hiss, but there is another explanation, which, again, Weinstein overlooks even though the information was available to him at the time he was writing Perjury.

Some Possible Explanations

Still, a mystery remains. How did Whittaker Chambers come to have any information at all – even distorted and innacurate information – about Donald Hiss and Harry Bridges, since the discussions about Hiss’s involvement in the case occurred nearly a year after Alger Hiss swore he had broken off contact with Chambers? Donald Hiss testified before the grand jury that he didn’t think he had ever mentioned Reilly’s offer to his brother. “I have lain awake at nights trying to figure out how he could have gotten any information along those lines,” he said. “As I understand his testimony, the information is wrong. I know he did not get it from me.”

There is at least one intriguing possibility – still speculative – which might also suggest how Chambers was able to get the State Department documents used to convict Alger Hiss. Donald Hiss said Reilly had sent a memorandum to Frances Perkins, then Secretary of Labor, suggesting several people as potential candidates to be Hearing Officer. One of the names on the list was Donald Hiss’s. This occurred in the spring of 1938. Donald Hiss said that Francis Sayre, Alger Hiss’s State Department boss at the time, might also have been brought into the discussion, since Donald Hiss was also working for Sayre. It was possible, Donald Hiss said, that Sayre also received a memorandum on the subject.

If Sayre did get a Bridges memo, it would have reached his office around the same time as other documents that Chambers collected from Sayre’s office and produced ten years later as evidence against Alger Hiss. (That batch of documents – later called the “Baltimore Documents” – all bore dates between January 5 and April 1, 1938.)

But if Alger Hiss didn’t hand these State Department papers over to Chambers, how did they reach him? A 1969 interview with Ella Winter, a journalist and former acquaintance of Chambers, provides a possible answer. Speaking to John Lowenthal, an attorney and author, she recalled that, in the 1930s, Chambers had once asked her to steal documents for him. According to Winter, Chambers said that taking State Department documents was an easy matter. All she had to do was make an appointment with an official (he suggested someone in the Trade Agreements section, where several of the documents used as evidence against Alger Hiss originated). If during the conversation the man got up to use the bathroom, she could scoop up any documents sitting on his desk.

Winter refused, but never forgot the request. If Chambers did ever personally employ this technique – and if it worked – it might explain both how he had found out about Donald Hiss and the Bridges case, and how documents from Alger Hiss’s office had come into his possession.