Charge and Countercharge

This succinct synopsis of the highly complex Hiss case is excerpted from Hiss’s 1978 coram nobis petition to have his case reopened. It was prepared by Victor Rabinowitz, who represented him in this action.

On August 3, 1948, Whittaker Chambers testified at a hearing of the House Un-American Activities Committee that Alger Hiss, while he was a government employee, had been a member of an “underground” group of the Communist Party from 1934 to 1937. At the time Chambers made his charges, Hiss was president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, after having rendered distinguished service to the government. His career in the State Department and his close association with the Yalta Conference and the United Nations, made him a prominent target for the anti-Truman forces. His conviction quickly became a political issue and, for some, a political bonanza. (As a result of the Hiss-Chambers investigation, HUAC member Richard M. Nixon, then an unknown freshman Congressman from California, became a national figure.)

Hiss responded to the Chambers charge by requesting an opportunity to appear before the Committee. He did so on August 5th. He denied knowing a man named Whittaker Chambers but, at a later session, confronted Chambers and identified him as a freelance journalist he had known casually from about 1934 to 1936 by the name of “George Crosley.” Hiss denied he had ever been a member of the Communist Party. When Chambers repeated his charges outside the privileged arena of the House Hearings, Hiss sued him for libel in the United States District Court for the District of Maryland.

Up to this point, Chambers had made no claim in his several appearances before the House Committee (or in his many interviews with the FBI) that any government documents had been given to him by Hiss. On the contrary, in his appearance on October 14 and 15, 1948, before a federal grand jury looking into possible communist subversion and violation of espionage laws, he testified that he had no knowledge of any government employee furnishing information to the Communist Party.

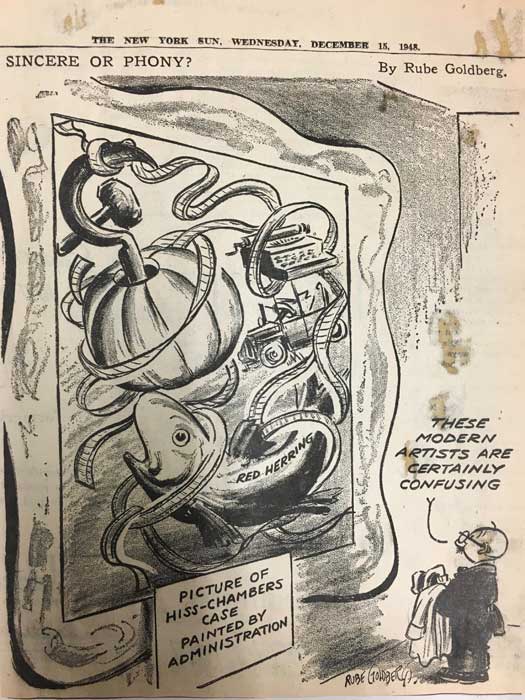

In the pre-trial proceedings in the libel suit, on November 4 and 5, 1948, Chambers was called upon by Hiss’s counsel to produce any papers he might have received from Hiss. On November 17, 1948, he produced four penciled memoranda in Hiss’s handwriting, allegedly relating to State Department business, and 65 typewritten pages. The latter purported to be copies of, or summaries of, 43 State Department communications which Chambers said were given to him by Hiss between January 1, 1938 and about April 15, 1938. These papers became known as the “Baltimore Documents.”

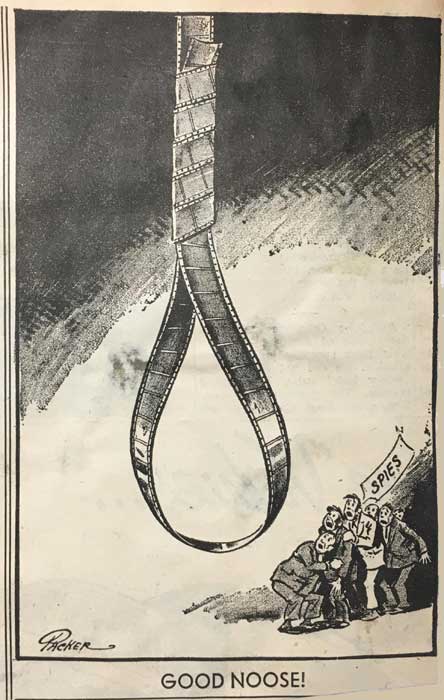

On December 2, 1948, Chambers delivered to the House Committee two strips of developed film and three undeveloped rolls of film. The developed film contained pictures of government documents that Chambers said he had received from Hiss. The films became known as the “Pumpkin Papers,” because Chambers had hidden them in a pumpkin prior to delivery to Committee agents. The production of these papers and film resulted in Chambers being called back before the grand jury then sitting in the Southern District of New York. The panel was conducting an investigation into the possible violation of espionage laws. Hiss appeared willingly before that same grand jury to respond to Chambers’ charges. He testified on seven or eight occasions from December 7th to December 15, 1948. On this final day – which was also the last day of the life of the grand jury – the jurors voted to indict him for perjury immediately after his final testimony.

The indictment was in two counts. The first count alleged that he had testified falsely when he stated that he had not turned over any secret, confidential or restricted documents to Whittaker Chambers, whereas in fact he had given such documents to Chambers in February and March, 1938.

The second count alleged that he had testified falsely when he said that he thought he could definitely say that he had not seen Chambers after January 1, 1937, whereas in fact he had seen and conversed with Chambers in and about February and March, 1938. After the usual pre-trial proceedings, the case came on for trial before Judge Samuel H. Kaufman and a jury on May 31, 1949. It ended in a mistrial on July 8, 1949, when the jury was unable to agree on a verdict. A second trial before Judge Henry W. Goddard and a jury began on November 17, 1949. Whittaker Chambers was the prosecution’s principal witness and the only witness with regard to many of the accusations it sought to prove. The following is the substance of Chambers’ testimony at the second trial:

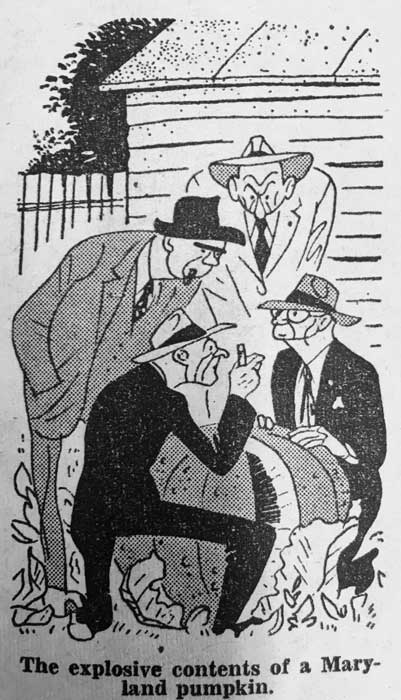

“Spy Hunt Plot Thickens,” Cartoon by Herblock (Herbert Lawrence Block), Washington Post, December 12, 1948

In 1934, Chambers was in Washington, D.C. as a member of a Communist Party “underground” and in that capacity first claimed to have met Hiss at a “restaurant in downtown Washington.” The introduction was allegedly effected by Harold Ware, who was described as the organizer of a Communist underground apparatus in Washington, and by J. Peters, who was described as the head of the underground of the American Communist Party. Chambers testified that at the meeting it was agreed that Hiss was to be disconnected from the apparatus of which Ware was then organizer and to become a member of a parallel organization which Chambers was then organizing. He was introduced to Hiss as “Carl.” This meeting, said Chambers, marked the beginning of a close association between Chambers and Hiss, both on a social level and as Communist espionage agents – an association which he said lasted for about four years.

At the time of the alleged meeting at the restaurant, Hiss was counsel to a Senate Committee investigating the munitions industry (the Nye Committee). Hiss’s first assignment, according to Chambers, was to procure through the Committee confidential State Department documents that dealt with “some angle of the Munitions Investigation.”

In 1936, Hiss was transferred first to the Justice Department and then to the State Department. In January 1937, Chambers claimed that he arranged a clandestine meeting between himself, Hiss and a certain “Peter,” whose real name, Chambers found out years later, was Col. Boris Bykov. Chambers said Bykov was his superior in the Communist underground.

Chambers went on to say that, at that meeting, Bykov said that the Soviet Union needed help, and that Hiss could procure confidential documents from the State Department and turn them over to Chambers for transmission to Bykov. Soon after, Chambers said, Hiss began to take home State Department documents every week or ten days, which Chambers would pick up from Hiss at his home and take to Baltimore to be photograped, returning the originals the same night. In mid-1937, Chambers said, he instructed Hiss to have papers brought home every night and to have Mrs. Hiss (also allegedly a Communist) type some of them verbatim and paraphrase others. Hiss was also to bring home, and turn over to Chambers, originals of State Department documents coming to his desk on the particular days of Chambers’ visits. Hiss would also turn over handwritten notes about documents which he had seen but which, for some reason, he was unable to bring out.

After the photographing of the documents, the originals would be returned by Chambers to Hiss, to be restored to the State Department files. The typed copies, or paraphrases, and handwritten notes would be burned. The photographs would be turned over by Chambers to Bykov.

Chambers stated that in April 1938 he broke with the Communist Party and discontinued his espionage activities. But he retained some of the typed documents, handwritten notes, and exposed film which had come into his hands between January and April, 1938. In May or June, 1938, he left them in an envelope with his wife’s nephew, Nathan Levine. Levine testified that he kept an envelope given to him by Chambers from sometime in 1938 until November 1948, when he returned it to Chambers at Chambers’ request. Levine never saw the contents of the envelope.

In addition to these contacts claimed by Chambers during the period from 1934 to 1938 for espionage purposes, Chambers testified to frequent and intimate social contacts between the Hiss and Chambers families during this period, including several after January 1, 1937. These involved stays by the Chambers family at Hiss’s home, visits on various social occasions and various trips out of town.

The government’s case rested largely on Chambers’ testimony. As to the first count, Chambers was the sole witness who testified to the alleged falsity of Hiss’s statement, with one single exception (testimony by Mrs. Chambers as to a single meeting). The same was true of the second count. To corroborate Chambers on both counts, the government offered the handwritten and typewritten documents and developed film produced by Chambers as described above, together with testimony by an expert witness that Baltimore Exhibits 4-9 and 11-47 and certain letters, admittedly typed by Mrs. Hiss, had been typed on the same typewriter.

In defense, Hiss denied any Communist membership or affiliation, denied having given Chambers any State Department or other classified documents, and denied ever meeting J. Peters. He testified that in December 1934 or in January 1935, while he was counsel to the Nye Committee, Chambers came to see him, introducing himself as “George Crosley,” a freelance writer doing a series of articles on the munitions investigation.

At a subsequent luncheon meeting, Crosley-Chambers told Hiss that he was planning to move from Baltimore to Washington, to complete his articles on the munitions investigation, and he was looking for a place to live with his wife and child. Hiss sublet his apartment at 2831 28th Street, Washington, D.C. to Chambers for a few months; the Hisses had already moved to a house at 2905 P Street, the now unoccupied 28th Street apartment had some time left on the lease.

Before moving into the 28th Street apartment, the Chambers family spent a few days at Hiss’s P Street house. Chambers told Hiss that the van bringing their household effects had been delayed. Hiss met with Chambers a few times after that, the last contact being in the spring of 1936, when Hiss refused Chambers’ request for the latest in a number of small loans. Both Hiss and his wife denied any visits to any of Chambers’ homes; any visits by Mr. and Mrs. Chambers to Hiss’s 30th Street or Volta Place homes (the houses Hiss moved to after leaving P Street), and any trips with Chambers, except on one occasion, when Hiss gave Chambers a ride from Washington to New York. Throughout their acquaintance which, Hiss said, lasted only about two years, he knew Chambers only by the name of “George Crosley.”

In addition to denying Chambers’ testimony, the defense contended the following:

- that Chambers had left the Communist Party prior to April 1, 1938, the date of the last of the Baltimore Documents; and

- that Hiss had disposed of his typewriter prior to January 1, 1938, the date of the first of the Baltimore Documents.

Despite these contentions, the second trial ended with a guilty verdict on each count on January 21, 1950.

Hiss was sentenced to five years on each count, the sentences to run concurrently. After an appeal, Hiss surrendered to the United States Marshall on March 22, 1951, and remained in prison until his release in November 1954.

On January 24, 1952, while Hiss was in custody, he moved for a new trial on grounds of newly discovered evidence:

- that the typewriter placed in evidence by the Hisses, who thought it was their old typewriter, was in fact not the machine owned by the Hisses in 1934-38;

- that Edith Murray, supposedly a maid of the Chamberses, who was the only person to testify to any social relationships between the two families, had made a false identification; and

- that Chambers’ testimony that he had remained in the Communist Party until mid-April 1938 was false.

But the motion for a new trial was denied by Judge Goddard, and his denial was upheld on appeal. Hiss served out his full prison term, although he did receive time off for good behavior.

Between March 25, 1975 and September 10, 1976, Hiss made a number of requests of the Department of Justice, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency and other government departments, under the Freedom of Information Act, to release their files relating to him. These various government agencies subsequently began transmitting tens of thousands of files, often severely censored, to Hiss. Still, based on the evidence of governmental misconduct apparent in the files, Hiss, in 1978, filed a petition of coram nobis to overturn the 1950 guilty verdict. According to information in the files, the prosecution had a “mole” in the defense team and also hid information that would have helped the defense.

The coram nobis petition excerpted here was denied in 1978. Subsequent appeals were unsuccessful. As a legal proceeding, the Hiss case had ended. Each of the four parts of the website that follow focus on specific issues raised at trial: Chambers’ relationship with Hiss; the Hiss case typewriter; the documents in the case (the “Pumpkin Papers” and the “Baltimore Documents”); and testimony, statements and commentary by other people mentioned by Chambers that often contrast with or contradict his accounts.